I graduated from the Pacific University Master of Fine Arts in Writing Program in 2008. While I formally studied creative nonfiction during my two years at Pacific, the nature of the program is such that the passion, precision and craft elements that make any piece of writing successful are valued first and foremost — and however you get there, whether through poetry, fiction or creative nonfiction, is up to you.

Today, when I tell people what I value most about my education from Pacific, I tell them that the faculty passed on a reverence for words that was at once accessible and humbling. In other words, they empowered me to live the writing life to the fullest, but they also made it quite clear just how hard and deep my work would need to be in order to find success.

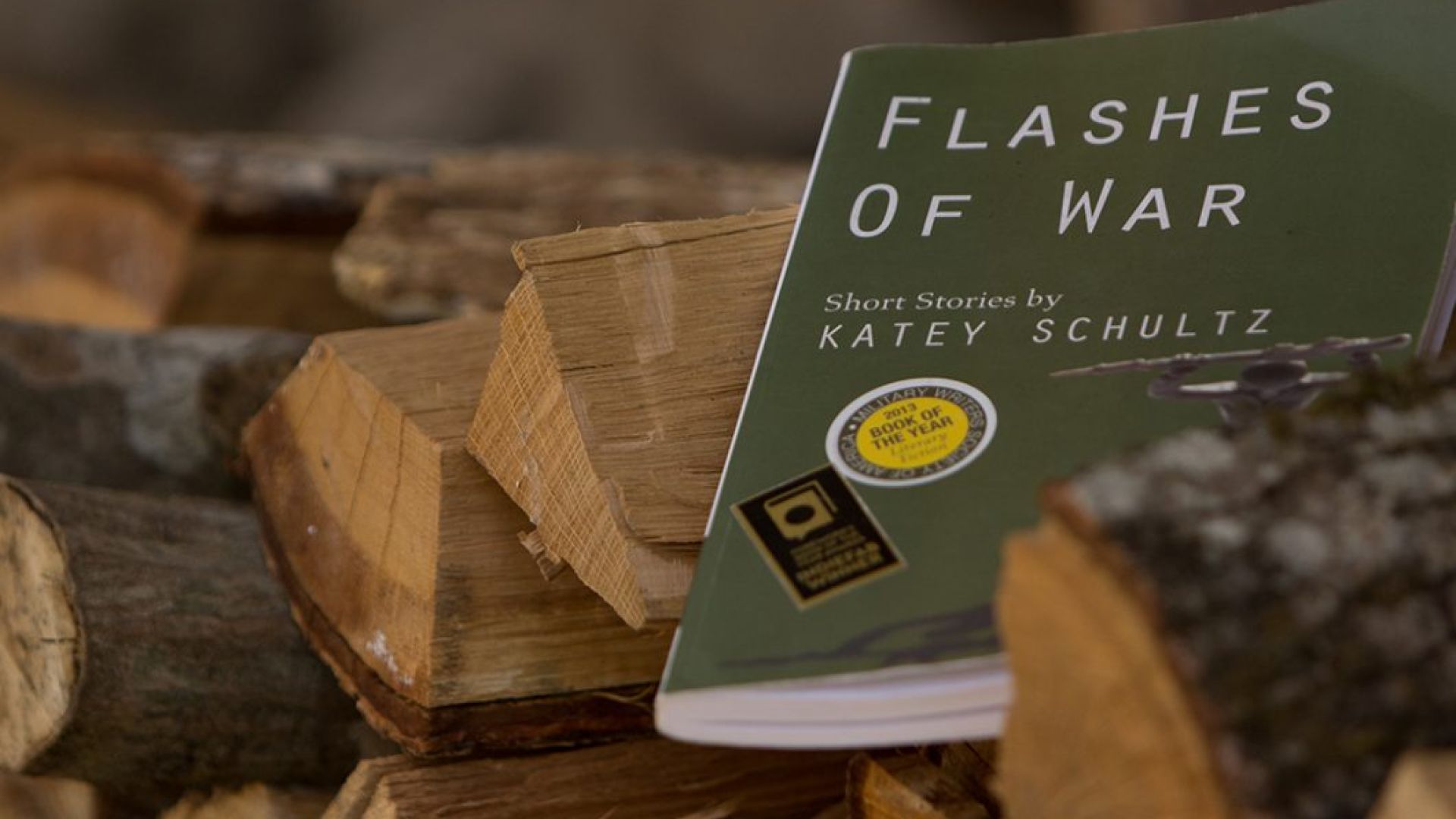

Five years after graduating, I held my first book of published short stories in my hands. The fact that it was fiction surprised a lot of people, but perhaps more surprising than anything was the fact that I had written a book about the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan — a book that proved so persuasive, I was routinely mistaken for a veteran and then, later, invited to address United States Air Force Academy cadets who read my book as a course requirement.

While working on Flashes of War, people often asked why I wrote fiction about this topic. The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan were described as “my generation’s,” but I knew very little about them and had no immediate ties to the military.

I am a civilian and have never travelled to the Middle East. Right or wrong, “their” side or “ours,” I wanted to know, on the level of basic human experience, what were these wars actually like?

How did people operate under extreme conditions with less-than-ideal tools for survival?

How did their personal traits influence their motivations and experiences against the backdrop of war?

What were the impacts of war inside the family home or in the far reaches of an individual’s mind?

I wanted to write my way toward answers to these questions by studying the intimate moments of a soldier’s or civilian’s life — images, decisions and thoughts so small and experienced under such strain that even an interview with the most forthcoming individual could not unearth.

I was not interested in becoming an embedded reporter or detailing the facts of either war through journalism. There are many writers who have done that and done it well. As someone inclined to make sense of the world through story, I knew my window into these wars would have to be narrative. What better way to begin than with unanswered questions and the creative freedom to write my way toward something I could believe?

I felt the stories brought me closer to something real and, if nothing else, could bear witness to the complexity of hope and suffering.

– Katey Schultz

As I researched and imagined, inspiration for stories in Flashes of War initially came in two ways: from the rhythmic and emotional quality of a quote or from the jarring contrast of a memorable image.

One example is a series of YouTube videos I watched with embedded reporter Ben Anderson. In an interview, a soldier looked into the camera and said, “America’s not at war. America’s at the mall.” I felt struck by the tension and cadence of this — the war versus the mall — and wrote my first war story titled, “While the Rest of America’s at the Mall.”

Another example came from the movie Kandahar, which included a scene depicting a group of Afghan civilians, each missing a leg and using crutches. The men raced toward a plane flying overhead that dropped half a dozen prosthetic legs from its hatch, sending them down on parachutes. When I saw this, I paused the DVD.

The countryside looked beautiful: rolling brown hills against a cloudless, azure sky. Then there were these legs silhouetted against the sun, these men hobbling toward them. This was a moment my mind could not comprehend, and I felt compelled to explore it by writing “Amputee” and “My Son Wanted a Notebook.”

To help immerse myself in the environment of war, I plastered my studio walls with quotes and photos. I used Google Images to “visit” Iraq and Afghanistan. In almost all cases, I was able to intersperse the stories with real locations, accurate historical or cultural references, and current facts.

I read books and watched countless hours of movies until the wars found their way into my dreams. I looked up weapons, order of military rank, Arabic and Pashtun terms, colors of uniforms. The list of new phrases at my disposal seemed endless: fobbits, ripped fuel, hot brass, haji, raghead, yalla yalla, got your six, pressin’ the flesh, stay frosty.

Likewise, primary accounts from civilians proved evocative:

“Since my brother was killed, I cannot taste my tea. I cannot taste anything.”

“I am but one fistful of dirt.”

“There is no law. The gun is law.”

Eventually, I filled myself with enough information to precisely imagine my way toward fiction I could believe in. I certainly didn’t have all the answers, but I felt the stories brought me closer to something real and, if nothing else, could bear witness to the complexity of hope and suffering.

Since Flashes of War was published in 2013, it has been celebrated by veterans, civilians, military families, war-lit authors, and everyday readers alike. I often Skype into book club meetings or classrooms across the country (for free — message me by clicking here!) and enjoy wonderful, lively conversations about authority, accuracy, and the writing life.

Students studying the book at universities from Germany to California, Washington to Massachusetts, are also thinking deeply about the work.

It’s important for writers and readers of any age and circumstance to understand that “write what you know” doesn’t just mean “write what you’ve experienced.”

Experience is not the only teacher. Empathy, the imagination, curiosity and research are also just as important. I’m honored to say that the faculty of Pacific taught me that, too.

This story first appeared in the Summer 2016 issue of Pacific magazine.