In 1945, Pacific University faced dramatic change — and some momentous choices.

World War II had come to an end, and a tidal wave of young people, mostly men, were coming home. The promise of a college education, abetted by the new G.I. Bill, beckoned.

But many universities, like Pacific, weren’t prepared to enroll all of them.

Universities in the United States had struggled through the war years. At Pacific, enrollment had languished. Faculty and staff wages stagnated. Building repairs were deferred.

But opportunity was emerging.

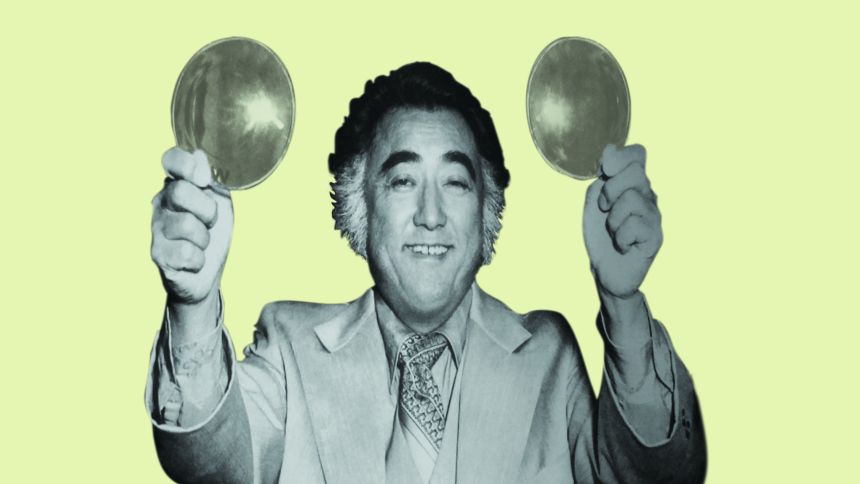

In Northeast Portland’s Hollywood District, the North Pacific College of Optometry sat shuttered after a couple of decades of operations. The owners, including Newton Wesley ’39, Hon. ‘86, wanted to revive it by affiliating it with a recognized institution of higher learning. They offered the charter, along with about $5,000 worth of equipment, to Pacific. In exchange, Pacific would operate the college, which was thought to be able to educate from 75 to 125 new students.

On Sept. 19, 1945, students started taking the first optometry classes in Marsh Hall on Pacific’s Forest Grove Campus in what would eventually become the College of Optometry, Pacific’s first health professions program.

Optometry Practitioners Fight Headwinds

In the middle of the 20th century, optometry was still seeking acceptance as a legitimate form of healthcare. Earlier in the century, optometrists were generally sneered at by the medical establishment, which thought of them as glorified jewelers. Indeed, early optometrists frequently operated inside jewelry shops, offering corrective lenses while their colleagues hawked bracelets and pendants.

"....optometrists were generally sneered at by the medical establishment, which thought of them as glorified jewelers."

Optometrists suffered “constant attacks” by medical groups as part of “their efforts to eliminate Optometry as a profession,” wrote Albert Fitch in his 1955 memoir My Fifty Years in Optometry. Fitch was among a band of optometrists who fought to turn back an effort by organized medicine to take over optometry as “a minor branch of medical practice.”

A 1914 letter to “brother optometrists” by Albert Myer, president of the American Optical Association, sounded a call to arms. “Tell your patrons that we are a body of technical experts who are developing a very important science — vitally important to them,” he wrote. “That the proud lineage of Optometry dates back to Copernicus and Galileo, and must not be shackled to Medicine.”

The optometrists’ resistance paid off. The practice gained stature, and accredited schools began to emerge. Major universities like The Ohio State University and the University of California-Berkeley began opening optometry colleges of their own. When Pacific University absorbed the North Pacific School of Optometry, it was the ninth such school in the United States.

Part of the push for more optometry colleges was the profession’s recognition that it needed new recruits. The Oregon Optometrist, the publication of the Oregon Optometric Association, said in 1945 that “optometry is losing ground, there being fewer optometrists today than they were 15 years ago.” If Pacific University could produce more optometrists, the editors argued, the entire Northwest would benefit.

Yet even at Pacific, optometry wasn’t wholeheartedly embraced. The university faculty at the time prided itself on offering a traditional liberal arts education and worried that by opening the doors to a school of optometry, Pacific would become a trade school.

President Walter Giersbach, who had presided over the university during the difficult war years, lamented this attitude. He noted that the optometry school had 200 applicants, but had capped the first class at 50.

“Two hundred students could have been brought on the campus. At $350 each, for instruction alone, the income of the university would increase $70,000 per year,” he wrote in his 1945 report. He called for Pacific to be bolder as it entered its second century. “We have the vision of a new day in education. We have the plans. We have the sturdy history so often coveted; what we need now are resources to make tangible the ideas and ideals which possess us.”

Willard “Wid” Bleything ’51, OD ’52, MS ’54, and later dean of the College of Optometry, praised Giersbach’s vision.“He saw the future,” Bleything said. “The vision people saw its value. The English Literature people didn’t understand. We weren’t training technicians: We were training people who care about people.”

Eyes Forward

In the 75 years since the College of Optometry opened at Pacific, the university has not only become a respected leader in research and practice, producing optometrists who practice around the world, but also in graduate and professional programs from healthcare to education to business.

From its hardscrabble origins, optometry has become a $17 billion industry, according to IBIS World, a market research firm. More than 37,000 people practice optometry in the United States, earning a mean annual wage of about $120,000, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Pacific’s College of Optometry has awarded more than 5,000 degrees, many of them doctorates in optometry. It also counts among its ranks 41 graduates from 1927 to 1944.

Today, the college serves about 400 students, including students on the doctor of optometry track, as well as in vision science master’s and PhD programs and in an emerging bachelor of applied vision sciences program that is providing optometry training for doctors in China, where optometry is not yet a distinct profession.

“We have a global view. We teach the full scope of optometry,” said Interim Dean Fraser Horn '00, OD '04. Pacific also has established a strong focus on vision therapy as well as a “contact lens team is one of the best in the nation, if not the world,” he said.

Optometry has become a cornerstone in a diverse spectrum of graduate and professional programs that build on Pacific’s liberal arts base. Students and faculty collaborate closely with the College of Education, where future optometrists can specialize in the impact of vision on learning, and the College of Health Professions, where optometry students connect with other allied health professionals as part of a comprehensive care team.