You would never know.

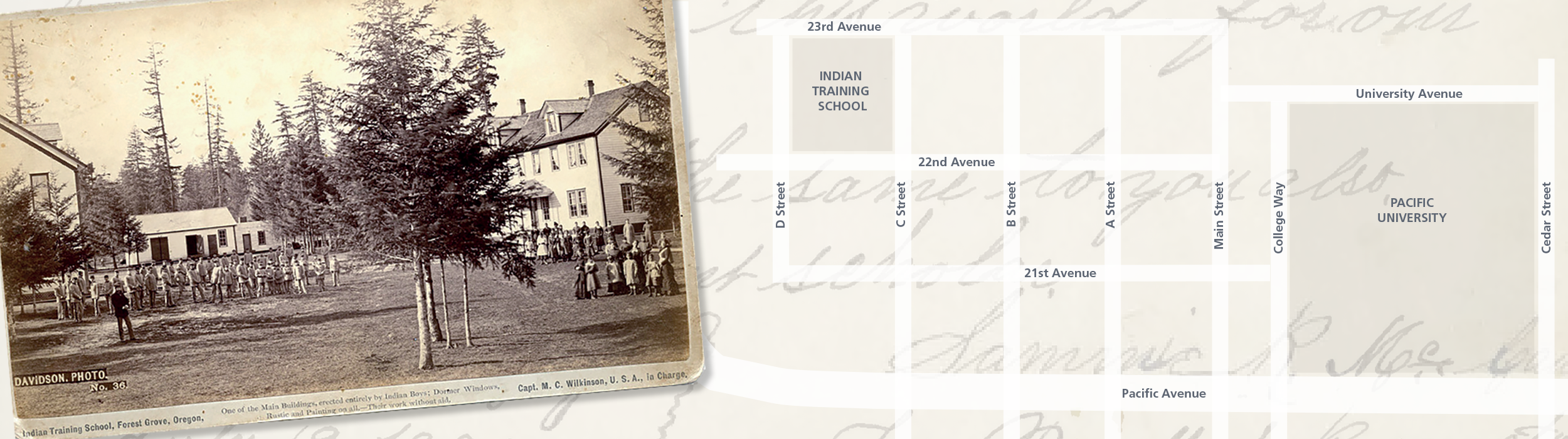

Today, the block in Forest Grove bounded by 22nd and 23rd avenues and C and D streets reveals nothing of its past. It looks much like the surrounding residential blocks, lined with tidy homes, sidewalks, shrubs and “beware of dog” signs.

You’d never know that this block was partly cleared 129 years ago by young Native Americans, who were brought to this quiet corner of northwest Oregon as part of a younger country’s drive to “civilize” them. You wouldn’t know these young people once fashioned leather into shoes, planks into furniture, and fabric into uniforms under the supervision of white men and women. You wouldn’t know that this unremarkable block once was the focus of a tug of war between Salem, Forest Grove and Washington, D.C. — a fight the locals eventually lost.

You’d never know that at least 12 young indigenous people died while they were being educated here.

The Forest Grove Indian Training School

From 1880 to 1885, this block was the home of the Forest Grove Indian Training School, a project backed by the federal government, political leaders, a former military officer — and teachers and administrators of Pacific University, whose campus was four blocks to the east.

The school was not officially part of Pacific, but the university supported the enterprise in many ways. As noted in a 1904 history that is stored in the Pacific University Archives, Pacific’s trustees exercised “a fatherly supervision” of the school, sending a delegation each year to visit the Indian school and report to the university. The trustees in turn passed their impressions to the Indian Department.

The Pacific connection started with a letter from the university’s Board of Trustees to the Secretary of War in 1879. The trustees called for the appointment of Army Lt. M.C. Wilkinson to the new post of military professor at Pacific. In Wilkinson, they saw an opportunity to bring federal money to Forest Grove.

They came to the school from the prairies and mountains, dressed in blankets and moccasins, with uncut and unkempt hair, as wild as young coyotes. They have already learned to sing like nightingales and work like beavers.”

— Harper’s Weekly

“Lieut. Wilkinson has placed before the Board of Trustees the purpose and plan of the Interior Department to educate at some institution upon this coast a certain number of Indian Youth of both sexes, and the Board of Trustees make this application for the detail of Lieut. Wilkinson, with the understanding that this Board of Trustees incur no pecuniary liability thereby, and that the government pay all the necessary expenses attending the same,” read the letter, which was copied into the written minutes of a board meeting.

The trustees’ pitch worked. Wilkinson, still considered an active-duty Army officer, started putting Pacific students through military drills, and the bureaucratic and political machinery started grinding to bring to Forest Grove the nation’s second federally funded, off-reservation Indian training boarding school, after the one launched in Carlisle, Pa., in 1879.

When the school opened, the leaders of Pacific, along with some local merchants who stood to benefit, considered it a victory. Many of the roughly 600 townspeople of Forest Grove, however, remained wary.

“Kill The Indian ... Save The Man”

People of European descent had settled into all parts of the country by the 1880s. Native people had largely been driven from the territories they used for centuries, herded on to reservations and forced to sign treaties drawn up by government officials. The remnant of the Tualatin Kalapuyas, who had lived near Gaston when missionaries like Tualatin Academy founder Harvey Clarke arrived in Oregon in the 1840s, were forcibly relocated southward to the reservation of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde.

In a country still healing from the wounds of the Civil War, the government aimed to find a way to secure a final peace with the people it had decimated with disease and warfare and driven from their lands.

The effort to resolve the unfinished business of settling the continent was wrapped in a belief that native people should be assimilated — cleansed of the characteristics and habits that distinguished their former lives and educated in the ways of white people. The Indian training schools were a manifestation of this effort. With the establishment of the Forest Grove Indian Training School, Wilkinson had most success enrolling children from tribes near Puget Sound, southeast Alaska and from east of the Cascades.

A particularly poignant pair of photos in the Pacific University Archives vividly show what it meant for native youths to leave their families to come to Forest Grove. An 1881 photo of new arrivals from the Spokane tribe shows 11 awkwardly grouped young people, huddled together as if for protection in an unfamiliar place. Some have long braids of dark hair; some girls wear blankets over their shoulders; some display personal flourishes, including beads, a hat, a neckerchief.

A second photo of the group is purported to have been taken seven months later, after the Spokane children had lived and worked for a time at the Indian Training School. In this photo, the same children are seated stiffly on chairs or arranged behind them. The six girls wear similar dresses; the four boys wear military-style jackets, buttoned to the neck.

Further, one girl is missing in the second photo — one of the children who died after being brought to Forest Grove, said Pacific University Archivist Eva Guggemos, who has extensively studied the history of the Indian Training School. The girl’s name was Martha Lot, and she was about 10 years old. Surviving records tell us she had been sick for a while with “a sore” on her side and then took a sudden turn for the worse.

The before-and-after photos of the Spokane children were meant to show that the Indian Training School was working: Young native people were being shaped into something “civilized” and unthreatening, something nearly European. But today the before-and-after shots appear desperately sad — frozen-in-time witnesses to whites’ exploitation of indigenous children and the attempted erasure of their cultures.

“Some white people who have visited this school and see what We Indian children have done and do, say With great astonishment, Did the Indian children do this?”

— The Indian Citizen, 1880s

Harper’s Weekly magazine published a story about the Forest Grove Indian Training School in 1882, telling readers: “They came to the school from the prairies and mountains, dressed in blankets and moccasins, with uncut and unkempt hair, as wild as young coyotes. They have already learned to sing like nightingales and work like beavers.”

Forced transformations like these played out across the country as America sought to deal with the nation’s original sin. When Capt. Richard Pratt, who founded the U.S. Training School and Industrial School in Carlisle, addressed a conference in 1892, he said this:

“A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one, and that high sanction of his destruction has been an enormous factor in promoting Indian massacres. In a sense, I agree with the sentiment, but only in this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.”

This was the context for the establishment and operation of the Forest Grove Indian Training School.

Native American Students In Forest Grove

Of the schooling itself, most of what we know derives from superintendents’ reports to the government, in letters and diaries written by teachers or administrators, and photos, which were often staged. These sources generally painted a rosy picture of what student life was like.

“Formerly the laundrying for the whole school was done by the girls and a Chinaman. The Chinaman struck for higher wages and an Indian boy was put in his place, and it was found he did equally well,” notes the 1884 superintendent’s report. “Since which time the number of boys in the boys’ laundry has been increased to five, and they now do about two-thirds of the washing for the whole school.”

One of the few sources of direct testimony from students at the time are the slim entries in a teacher’s autograph book, a collection of notes written by about 44 young students during their time in Forest Grove. Many are filled with brief Christian sentiments, reflecting the evangelistic education they received at the school.

“To dear teacher,” reads one. “We can write our names in albums in this sinful world of ours. But will our names be found in that album which will be open on the last day before the great judgement. Your kind and willing teaching will never be forgotten through life. Your obedient scholar, W.H. Wilton, Forest Grove, O., July 20th, 1881. From Puyallup Reservation.”

Also surviving in the Pacific University Archives is a single yellowed and tattered copy of The Indian Citizen, a single-sheet student newspaper. It notes practical things such as “During the past 4 months 493 garments, and 82 articles of household use, have been made, by an average of 10 girls, in No. 1 sewing room.” It also notes the formation of “The Indian Base Ball Club.”

The Indian Citizen has a lead editorial headlined “The Future of the Indians,” which speaks of the challenges indigenous people faced in the western United States in the 1880s.

“Most of the white people have an idea that Indians cannot learn or remember anything which they are taught. But a great many who think in that way have been greatly surprised when they see the intelligence of the boys and girls and see some articles which they can make and that they are as industrious as any white children can be. Some white people who have visited this school and see what We Indian children have done and do, say With great astonishment, Did the Indian children do this?”

Perhaps the most vivid account of life at the Forest Grove Indian Training School is contained in an 1882 letter written by a teacher, Mary Frances Lyman, to her parents, Reverend and Mary Lyman. She describes “an unfortunate incident” at the school.

“Obid Williams, the black sheep of the school, stole some money out of Hoxter's store. Over 100 dollars, and then telling Charley Abraham, one of the best Spokane boys, that he had a lot of money from home persuades him to run off with him. They stopped at Hillsboro and bought some clothes and then walked on toward Portland.

“Some of the Indian boys in pursuit got on the train here, and hid themselves over the train. Obid & Charley walked as far as Beaverton and then concluded they would ride the rest of the way. As soon as they got on the cars Ch. Varner the 1st Sergeant of the I.T. School stepped up and said 'Lets go home, Charley,’ then the rest of the boys showed themselves and they brought the boy back on the freight train. The boys who went after them showed considerable sense. The stealing was a very bad thing, and I fear will injure the school very much. The boys may have to be sent to prison, I don't know. I feel very sorry for Charley who is really a good boy and who felt very bad about it.”

The boys were returned to the school, but Obid (or Obed) Williams was sent to the state penitentiary to serve a sentence of a year. When he was released back to the Forest Grove Indian Training School, the superintendent put him on a train back to the Washington Territory.

Relocation To Salem

After Wilkinson was ordered to return to full-time active Army duty, Dr. Henry John Minthorn was appointed superintendent of the training school in Forest Grove. The educator and physician was a stern leader, as former Indian School student Henry Sicade wrote in 1917 to Samuel Walker of Forest Grove.

“I well remember how the doctor would use his fists and number tens instead of reasoning with the boys,” said Sicade, referring to the doctor’s hands and feet.

Minthorn is probably best known as being the uncle of future president Herbert Hoover, who lived with Minthorn’s family in Newberg and Salem beginning in 1885. As Hoover wrote later, “The doctor was a mostly silent, taciturn man, but still a natural teacher.”

Minthorn, a Quaker, preferred Newberg and Salem to Forest Grove, where Congregationalists held sway. Just a few months after arriving, he began to pitch the federal government on the idea of relocating the Indian Training School.

The stealing was a very bad thing, and I fear will injure the school very much. The boys may have to be sent to prison, I don't know. I feel very sorry for Charley who is really a good boy and who felt very bad about it.”

— Mary Francis Lyman, 1882

He succeeded in persuading the Indian Department, the Interior Department agency that oversaw Native American affairs, that the school should own enough acreage for the native students to farm. Officials in Salem offered the federal government a donation of 171 acres for the school and its farmland. Pacific and Forest Grove officials countered by offering real estate enticements of their own, but they couldn’t match Salem’s offer. The school moved from Forest Grove to Salem in 1885.

Minthorn quit the superintendent’s job a little before the move, going on to become the first superintendent of Friends Pacific Academy, the predecessor of Newberg’s George Fox University. He later moved to Salem.

The Indian Training School, known today as the Chemawa Indian School, still operates in Salem. It is the country’s oldest continually operating off- reservation boarding school for Native Americans. The school today says its intention is to “afford each student an opportunity to achieve his/her full potential as a shared success between themselves, parent and our community.”

Nothing remains to mark the school’s time in Forest Grove. Pacific converted the Indian Training School’s boys’ dormitory into its first dormitory for college men in the 1890s, but the land was sold and the former dormitory demolished in 1908.

Pacific Grapples With Its History

While Pacific did not pay for nor operate the Indian Training School, it supported its mission. It invited the school to open in Forest Grove. It leased, then donated, the land on which the school stood. It employed the first superintendent as a professor of military tactics. It supplied trained teachers to work in the school, and its trustees lobbied on the school’s behalf to government officials in Washington.

“I’ve always been drawn to exploring the horrible things we do to each other. And asking ‘Why don’t we learn from the past?’”

— Eva Guggemos, 2019

The presence of the Indian Training School now lives on mostly in the Pacific University Archives, where Guggemos has organized, cataloged and digitized some of the records that have been assembled through the years. Thanks to her efforts and those of her former student assistant Shawna Hotch ‘17, who graduated from the Chemawa Indian School and whose ancestor George Brown attended the Forest Grove Indian Training School, you can read digital images of the letters written by Wilkinson, Sicade and others associated with the school.

Among the more haunting items in the collection is the autograph book, which holds page after page of the careful cursive of the young students.

“My dear teacher,” reads one in careful, flowing script. “Remember me as one of your scholar. Yours faithfully friend, Chas. A. Thompson, from Nez Perce Agency, Idaho. August 17, ’83.”

Thompson died as a student, far from home, on March 13, 1885. The culprit was likely tuberculosis, the leading cause of U.S. deaths in that decade.

As university archivist, Guggemos has worked diligently to document this history. She has conducted extensive research on the Indian Training School, helped arrange exhibits, made public presentations and placed documents online. She is writing a book about the school that she hopes will be published in the coming 12 months.

“I’ve always been drawn to exploring the horrible things we do to each other,” she said. “And asking ‘Why don’t we learn from the past?’”

Guggemos has ideas about ways Pacific can acknowledge its part in establishing and supporting the Indian Training School. For example, she thinks the site of the school should have a historical marker.

She suggests Pacific should reach out to the tribes of students who died at the school, asking their input on how to better acknowledge and care for the unmarked graves that exist in the Forest View Cemetery in Forest Grove. Pacific has reached out, in a separate effort, to local tribes to discuss the return of Native American artifacts held by the university.

And, Guggemos thinks Pacific can make constant, public acknowledgement that it is built on land where native people were pushed out. The first such acknowledgement took place at the May Commencement ceremonies.

Today, historians and Native groups are examining the legacy of the training schools, which caused children to be separated from their families in order to be shaped into something like white men and women. While the schools caused lasting damage to native families and tribes like the Puyallup, the Piute, the Nez Perce and the Spokane, they did not succeed in “killing the Indian.” In fact, native people are reclaiming their culture and history in the Northwest and elsewhere.

Stan Uentillie ’97, a Pacific alumnus and a member of the Navajo tribe, whose parents worked at Chemawa and attended federal boarding schools for 12 years, attended Guggemos’s recent public presentation on the Indian Training School.

When it was over, he took the microphone.

“The sun, the moon, the stars, the weather ... are the only things that haven’t been taken from us,” he told the hushed room. “No more saying we’re sorry. That doesn’t cut it anymore."

Special Thanks to Eva Guggemos, Archives/Special Collections Librarian—historic references and photos.