Five-Ring Politics: Boykoff Studies Darker Side Of The Olympics

When the opening ceremonies at the 2024 Olympic Games in Paris float down the River Seine, most of the world will be focused on the pageantry, pomp and circumstance surrounding the spectacle of sport held every four years.

When the opening ceremonies at the 2024 Olympic Games in Paris float down the River Seine, most of the world will be focused on the pageantry, pomp and circumstance surrounding the spectacle of sport held every four years.

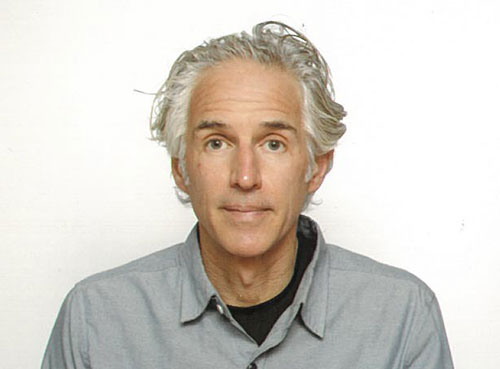

However, Pacific University politics and government professor Jules Boykoff will focus on the political and humanitarian side of the Games that most people don’t see.

Boykoff and his writing partner, Dave Zirin, will travel to Paris later this month to author several articles for The Nation magazine documenting the political and humanitarian issues that not only surround Paris’ efforts to host the Games but also those of the Olympic Movement, which Boykoff has studied for the last 15 years.

“We’re going to go behind the scenes of the Olympic spectacle and figure out what is going on there,” Boykoff said. “We will talk to people who lose their homes because of the Olympic Games. We will talk to those who track the big environmental promises that Olympic organizers made and help us understand whether those promises are reality. We will talk to people across the political spectrum whose lives are affected by the Olympics.”

While hosting the Olympics provides a city and country the chance to showcase itself on the world stage, Boykoff points out that it is often at the cost of the citizens of the host city and more on the city’s marginalized populations affected by efforts to host the Games. This is the third time Paris has hosted the Olympics, but just the first time since 1924.

Those concerns are part of a larger truth, Boykoff says, that sports are simply politics by other means. There is no way to separate the two. He explains the intersection in his most recent book, What Are The Olympics For?, published in March by Bristol University Press.

“If you take a close look at the Olympics, that becomes glaringly apparent,” Boykoff said. “If the Olympics aren’t political, why do all of the athletes march into the opening ceremonies by country, thereby inflaming political nationalism? They could just as easily enter by sport, spotlighting peaceful internationalism instead.”

Surrounding the Paris Games, Boykoff points to approvals by the French government to use artificial intelligence surveillance as part of its security measures, years before the rest of the European Union. The clearing and relocation of unhoused individuals and asylum seekers to clean up Paris streets. And even studies that the Seine, which will host the opening ceremony and open-water swimming for the triathlon, continues to test for unsafe levels of E. coli, despite $1.5 billion spent to clean up the famed river.

Those issues are on top of criticism of the International Olympic Committee on the inclusion of athletes from Israel in the midst of the Israel-Palestinian conflict while athletes from Russia continue to be banned from participating as part of the Russian Olympic Federation.

While the concerns have occasionally bubbled up in mainstream media, they are far from new. Boykoff experienced several protests, specifically around enhanced policing techniques, when he visited Paris in December. While the government has a sunset date of March 2025 for the technology, many believe that the period will be extended indefinitely.

“I attended protests by both the right and the left,” he said. “There’s real concern across the political spectrum around these surveillance measures. And when you look at the history of the Olympics, these tend to stick around in the wake of the Games and become part of normal policing.”

In terms of environmental issues, Boykoff witnessed similar water quality issues during the 2016 Olympics in Rio de Janeiro. Triathletes swam in Guanabara Bay, whose water quality was categorized by the World Health Organization as poor to very poor.

“The Olympics talk a big environmental game but their follow-through is consistently lacking,” said Boykoff, who was also on location for the 2012 London Games and in Japan in advance of the 2021 Games in Tokyo. “Rigorous social science research shows that even as the rhetoric around green environmental measures has increased, the follow-through has actually decreased.”

While Boykoff is critical of the Olympic movement and has studied the politics and financing of the Games since 2010, he is careful to emphasize that he supports the athletes. A former member of the U.S. Under-23 Men’s Soccer National Team, he believes that his background as a former national team, professional, and NCAA Division I soccer player lends more credence to his analysis of the inner workings of the Games and how they affect competing athletes.

“My approach to the Olympics is that you can do two things at once. You can support the athletes and you can fight alongside them to get the bigger piece of the money pie that they deserve,” Boykoff said. “You can still critique a lot of the entrenched downsides of the Olympic Games that tend to stem from the IOC and local organizing committees.”